Wearable Art & Conceptual Clothing

BY JESSICA HEMMINGS

Fashion Theory: Wearable Art and Conceptual Clothing

Contemporary textile art has found two seemingly discrete applications for the garment. One is the Wearable Art movement that produces handcrafted clothing for sale through galleries, boutiques and specialist fairs. The other is Conceptual Clothing, sculpture that takes the garment as its form and often uses textiles as its medium. While Wearable Art and Conceptual Clothing initially developed distinct personalities suited to their roots on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, the influence each has had on the other has rendered these respective boundaries increasingly obsolete.

Wearable Art first surface in the United States during the counterculture years of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like the spirit of the time, handmade clothing was a form of creative expression that rejected the seeming conformity of the previous generation. Reacting against the use of synthetic fibres and mass production, Wearable Art sought to express individuality through handmade clothing. Today, the movement has grown away from some of the idealistic roots of 30 years ago and now defines a high-end style of clothing that is to varying degrees handmade. The prices necessary to support the labour intensive design work and the prestige of one-of-a-kind production have ironically returned Wearable Art to some of the values the origins of the movement sought to undermine. Nonetheless, Wearable Art continues to attract clients who have both the means to afford and the desire to make an individual statement through dress.

In comparison, Conceptual Clothing investigates political and social concerns associated with identity through sculptural representations of the garment. Prejudice is often linked with appearance, and dress in particular id often assumed to be representative of identity. Of Conceptual Clothing, Mildred Constantine and Laurel Reuter write in Whole Cloth that “Parallel to the development of art within the fashion world, and to the flourishing of a Wearable Art movement, was a third and even more pervasive force: artists who make art through the vehicle of clothes.” Early examples of Conceptual Clothing were often made by artists with a Fine Arts background who chose dress and its relationship to identity as a sculptural theme.

Nina Fleshin, curator of the 1993 “Empty Dress: Clothing as Surrogate in Recent Art” explains that “Artists today represent clothing a abstracted from the body, in order to investigate issues of identity.” For the empty garment, the ghost of the wearer is inescapable. Radical and sexual prejudice and, particularly in the 1980s, the devastating effects of the AIDS epidemic in Europe and America, have made the empty garment a particularly poignant image. The influential exhibition “Conceptual Clothing” was curated in 1987 by two artists, Fran Cotteii and Marian Schoettie. In their catalogue they described how “… a representation of clothing in isolation from the figure invites the viewer to… merely try on the work. It’s in this intimacy, this invitation to participate with the works and make them complete, that clothing is such a powerful vehicle for artists… This outer layer can often reveal and communicate more than the body itself.”

Alongside a sense of loss or absence, the empty garment can also allude to concealed or ignored identities. In other cases Conceptual Clothing affects a distance between object and viewer through the use of materials that disrupt preconceived notions of dress.

Wearable Art and Conceptual Clothing shared in their rejection of a mutual bedfellow – fashion. Textile curator and conservator Melissa Leventon notes, “In many ways, wearable art has more in common with contemporary fibre than it does with designer fashion.” Leventon notes the reluctance of museums to collect Wearable Art, contrasted with the general acceptance of costume and high fashion collections, and links this prejudice to the long-standing unease towards the field of craft within the arts community. Fashion, whether couture or high street, clothes most of our bodies on a daily basis. But while this familiarity makes the shape of the garment resonate with the personal and the intimate, the investigations of Wearable Art and Conceptual Clothing use this familiarity for very different ends than that of fashion.

Wearable Art is in fact premised on ideals that conflict with many of the values of the fashion industry. Reluctant to aspire to the rapid turnover generated by seasonal collections, pieces are based on quality rather than quantity, timeless rather than fashionable. Leventon notes of Wearable Art that there is a “far greater interest in producing the textile than in producing the garment, and the materials often convey the meaning of the piece.” Emphasising fabric rather than the tailoring, Wearable Art pieces often incorporate large areas of uncut fabric that do not lend themselves to specific sizes or a tailored look. Pieces such as Jeung-Hwa Park’s knitted scarves are clearly based on a desire to produce functional fabrics that rely on a sophisticated command of chosen materials and techniques with minimal interference with the fabric structure itself. Glasgow based designer, Jilli Blackwood, is one of few designers to produce handmade one-of-a-kind garments with emphasis not only on fabric surface but garment shape as well. Blackwood’s fitted designs may signal a new trend in Wearable Art, one in which fabric is no longer the single emphasis, but tailoring and shape play an important and complementary role.

Despite a sound ideology, today the Wearable Art movement experiences only a fraction of the enthusiasm it has generated in past decades. A down-swing in the economy has been blamed for the closing of several boutiques instrumental in the early years of the movement. The ease of low overhead internet-based business has also been blamed although textiles may be one of the least served fields when it comes to the benefits of the internet. Texture and handle have yet to find true replication through the internet but there are perhaps other more widespread reasons for the faltering interest in the field. Many have noted that we do not live in a time that values the skills of hand production. We do live in an age that quietly celebrates conformity and spends little time nurturing individuality. I would suggest that Wearable Art continues to find its greatest following in the United States because it stands in such contrast to the mainstream options for clothing. The Martha Stewart/Gap T-Shirt aesthetic seen in the ubiquitous malls spread across the country has a healthy and largely unchallenged following.

Conceptual Clothing has benefitted from a modicum less prejudice than Wearable Art’s uneasy connection with the crafts. While Wearable Art struggles for publicity outside the handful of bi-monthly and quarterly magazines that cover contemporary textile art, Conceptual Clothing has had some success sneaking into the greater selection of sculpture and contemporary art publications available. That said, the hallowed walls of the white cube operate with their own distinct notions of the acceptable and unacceptable, often making it difficult for artists who work with textile materials to receive equal attention unless the work is one of several more traditional sculptural materials that they regularly work with. On the whole, Wearable Art has risen to many f the theoretical challenges that Conceptual Clothing engages with. In turn, Conceptual Clothing engages with many of the themes that brought about the Wearable Art movement: conformity, beauty, and an individual expression of identity through dress. At times these investigations appear on a material level; for others, clothing, whether worn or exhibited in a gallery, offers an ideal site to question a complacent world view.

Shelly Goldsmith’s “No Escape: Reclaimed Dresses from the Children’s Home of Cincinnati” (see Embroidery July 2002) uses the surface of the garment to print seemingly disconnected images of natural disaster. For Goldsmith, the surface of the dress acts as a picture plane; identity is established through the size of the dress. Celebrated Wearable Art designer, Tim Harding, muses on the nature of surface, explaining “In painting the picture plane is the window through which the audience must look to experience the artist’s vision. That plane is also perhaps the ultimate barrier between art and life. Can the artist ever break that barrier and involve the viewer in the creative act; can the viewer ever be “in” in the work? Consider, that to make a painting in the form of a garment allows a viewer to literally step into the work, wrap it around themselves, feel its weight on their shoulders and its texture in their hands.” Harding’s entirely wearable and aesthetically pleasing garments are born out of a theoretical inquiry into conceptual and art historical concerns. Speaking of his own functional designs, Harding sees Wearable Art as an opportunity for surface to envelope the viewer and establish a visual rapport between the two.

Galya Rosenfeld’s garments investigate the very snaps and seams that make a garment hang together. Textile structures come under myopic scrutiny, assembling easy-to-alter dresses out of strops of snaps and poppers. Like Jueng-Hwa Park’s knits Rosenfeld explains that several of her designs are assembled without any stitching. Instead, two continuous lines of cotton twill snap-tape are “gridded” around the body to create fabric and dress form simultaneously. As Rosenfeld explains, “Each snap allows for rotation at a bias angle, allowing the dress form to fit the shape of the wearer”. By taking apart the mechanics of dress making, Rosenfeld creates Wearable Art that is drive by conceptual inquiry.

Projects such as Brian Janusiak’s knitted sweaters are equally ambiguous. Described as “portraits of an extended moment for a series of individuals”, Janusiak conceived of the idea to collect data from personal computers that record frequency and type of computer use and to transfer the graphic representations of these codes onto sweaters. Concept was transferred directly to a group of knitters who produced the garments just as they would any other pattern they received. Janusiak conceived of the project as a performance of sorts. Rather than the empty garment, the exhibition opening of his show included project participants who wore the sweaters made from their computer codes mingling with the viewers – literally identity worn across the chest. In Janusiak’s words, “The project is in part a questioning of what can and cannot be assumed by pure information alone determining who any of us are in the world. It is also an examination of the beauty inherent in one’s actions over time as they create patterns that define us.”

Concept and function are also combined in work such as London/Delhi based partnership Blank, who explore the possibilities of using recycled cloth in high-end clothing and accessories. Recycling moves from a purely thrifty motivation of function into the boutique world of one-of-a-kind accessories. Charlie Thomas takes the concept of recycling full circle with a series of garments and accessories made entirely from paper. Here it is the skill of the maker, craft values as well as concept driven design based on a material investigation that is of interest. Also working with paper, Deborah Bowness uses images of garments as wallpaper patterns. Rather than the orderly repeat of traditional wallpaper, Bowness has created an ironic simulacrum of disorder. The wallpaper can be read as a political statement about the “surface” interests of dress and fashion as well as the novelty apparent when the normal is viewed from an altered perspective, certainly functional, but impossible to wear. Finally, designers such as Nick Cave stretch their conceptual wings even further with projects such as his wild variety of “Sounds Suits” designed as performance art pieces. They too are dis-served by name-calling and boundary building and are often concept driven but fashioned for the body rather than sculpture in the round. As with the tired “art versus craft” debate, there is increasing agreement that boundary building is in the best interests of neither discipline, so too the demarcations between Wearable Art and Conceptual Clothing are increasingly indistinct.

Embroidery magazine, November 2003: 12-17.

Conceptual fashion

Wearer-collectors looking for that spark of originality are being drawn back to the early works of fashion’s Japanese and Belgian “troublemakers”, says Avril Groom

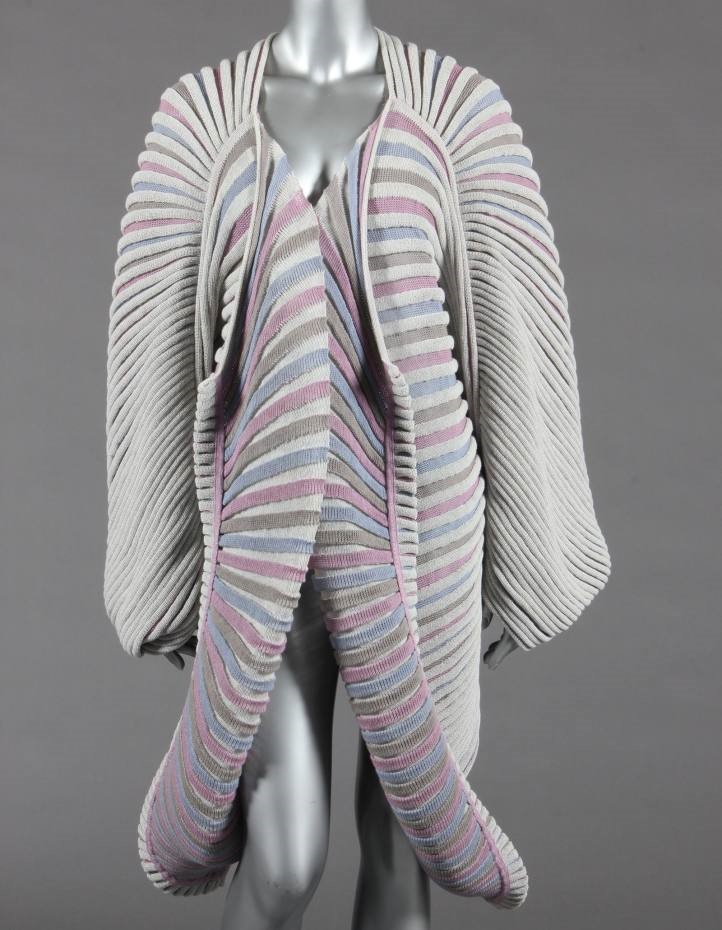

Issey Miyake cotton, linen and nylon Shell coat from 1985, sold for £۳,۰۰۰

Young designers looking for inspiration are understandably drawn to the forgotten areas of fashion – clothes from periods currently out of favour, of which they have no experience and so view with fresh eyes. This is one way in which trends evolve, and in a recent discussion with Britain’s premier vintage-clothing auctioneer, Kerry Taylor, I asked which styles are now coming back into focus and would therefore be good to buy.

Junya Watanabe for Comme des Garçons polyester skirt from the 2000 Techno-Couture collection, sold for £۵,۵۰۰, Kerry Taylor Auctions

Taylor’s recent book, Vintage Fashion & Couture: From Poiret to McQueen, looks at the style and collectability of fashion from the 1900s to the 2000s. She devotes a section to the nonconformist conceptual designers of the 1980s and early 1990s – mainly Japanese and Belgian – who, she says, “regarded fashion as an applied art… [making] complex and deconstructed clothes where it can be a challenge deciphering back from front”. Work by the names involved – notably Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons and her protégé Junya Watanabe, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, Maison Martin Margiela, Ann Demeulemeester and Hussein Chalayan – is still fairly affordable, but Taylor feels that as the trend is ripe for revival, that is set to change.

Lo and behold, young designers such as JW Anderson and Christopher Kane were clearly influenced by conceptual cutting and innovative fabric technology for their spring 2014 collections, and the close pleating pioneered in the 1980s by Miyake is ubiquitous for the new season. According to San Francisco-based vintage-fashion dealer Ricky Serbin, who sells through 1stdibs, as long as four years ago several American designers were buying collections of Miyake pieces from him to use as inspiration. (Current conceptual stock includes a double cashmere and leather coat by Margiela for Hermès, $2,400).

Hussein Chalayan cotton dress from the 2000s, sold as part of a lot for £۴۵۰, Kerry Taylor Auctions

At present, Taylor expects 1980s designs from the Japanese big three (Comme, Yamamoto and Miyake) to fetch at least £۱,۰۰۰, although prices are rising steadily – a 1982 Comme coat made £۴,۸۰۰ in 2012, while a similar model fetched only £۲,۸۰۰ in 2006. Her greatest coup has been an iconic 1991 Yamamoto wooden dress, sold to a museum for £۴۰,۰۰۰ in 2010; an equally signature Margiela “mannequin” bodice was comparatively cheap last year at £۱,۸۰۰٫ There are still bargains to be found, though – American dealer Jennifer Kobrin, who sells on 1stdibs, has a 1990 lace-trimmed Comme dress for $750 and a fringed Miyake coat for $1,200. Taylor recently sold two Chalayan dresses from 2000 for £۴۵۰; his conceptual showpieces are, she says, “so rare we never see them”.

Comme des Garçons lace dress, $750, from Jennifer Kobrin on 1stdibs

Carmen Haid, founder and creative director of vintage-fashion emporium Atelier Mayer, believes some owners of such pieces may be “sitting on them, expecting a major retrospective exhibition that will push prices up”. Conceptual clothes can be a hard sell because they sometimes lack hanger appeal, she continues, “though early Margiela, Demeulemeester and Galliano are collectable – usually at least £۱,۰۰۰ – along with Yuki, the London-based Japanese designer who became famous for his pleated designs in the 1980s. His pieces are very wearable and sell fast.” She currently has a striking salmon-coloured Yuki dress for £۱,۸۵۰٫ Not all fans are just looking for investment value, however. “In the 1980s I used to wear only the Japanese designers, whose ethnically based work related to the Iranian tribal menswear styles that I loved,” says Shirin Guild, who designs modern kilims, handmade in the mountains of Iran, as well as cashmere items. “I had an eye for their key pieces – simple and easy – which I still have and wear, mixed with my own designs.”

Collectors who buy conceptual styles to wear often have a particular mindset. “They are looking for that spark of originality and freedom of thought,” says Gill Linton of Byronesque, which was set up a year ago and specialises in contemporary-designer vintage. “They love the ‘troublemakers’ – the Japanese with their tricky shapes mixing their traditions with western history, the deconstructionists from Kawakubo to Margiela and early Galliano, turning the conventions of clothes-making on their heads.” Current items include 1980s draped trousers ($745) and a cashmere coat ($2,200) by Miyake, a 1990s tailored jacket by Yamamoto ($830) and a 1990s “garment bag” coat by Margiela ($1,650). Until recently, conceptual pieces have sold, Linton says, “to a close group who really get it”. Many of them, Serbin adds, “are collectors who buy both to wear and keep – often complete collections of a designer’s work. A recent cache of 50 Miyake pieces sold very fast.” The designers are still familiar labels, but their early work is the most collectable, especially where the creator has since, like Margiela, left the company or retired, as has Demeulemeester.

Kobrin says, “Artisanal pieces by Margiela [from about $3,500] and early pieces by Kawakubo and Miyake are highly collectable – the more unique the better, so the very well-known Miyake pleated pieces are less sought-after. As investments, key Comme des Garçons pieces are making big amounts at auction and early Margiela prices have gone up since he left.” ۱stdibs fashion director Clair Watson held a Margiela sale in New York three years ago with site member Resurrection, and a Japanese sale a few months ago – both attracted keen interest, although, she says, “they are still something of a wild card, not quite out there yet, so still worth buying, and a very individual look”.

Young designers and museums notwithstanding, the current core market is still the passionate wearer-collector, such as architectural stylist Regina Drucker. “I have a wonderful selection of Issey Miyake’s work that I won’t term vintage, but art,” she says. “I have an iconic early 1970s linen jumpsuit, as modelled at his first New York show, and a rare 1990s Staircase dress of pleated fabric with the sides like steps ascending. I love the avant-garde aspect of wearing art – not mere clothing, but an artist’s vision rendered tangible in textile. Also, they travel well… a ready elegance without ironing.”

.

www.jessicahemmings.com

www.howtospendit.ft.com

Embroidery magazine, November 2003: 12-17

فارسی

فارسی